Speed is one of the most common and least helpful words in running, perhaps second only to tempo.

Both are nebulous, hand-wavy, “you know what I mean” words that get slapped onto various runs and only serve to confuse otherwise coherent conversations.

If you told a room of 10 runners that you’re off to do some speedwork, there would probably be 10 interpretations.

So, today, let’s talk about speed: what it is and isn’t, why it matters, and how we develop it.

Key Takeaways

When training for a race, speed refers to running faster than race pace.

Speed can be categorized into four types: pure, general, supportive, and specific.

Specificity is key—effective training should target your primary performance limiters.

For most recreational runners, speed is not a primary performance limiter.

Many runners spend too much time developing general speed, which is not the best use of training time.

Developing pure speed has multiple benefits.

Improvements in pure speed enhance other categories of speed and endurance.

Pure speed training can (and should) be developed year-round, regardless of race goals.

Implementing pure speed training can be straightforward—skip to the end for practical applications.

What is Speed?

Before we go any further, I want to be clear that we’re talking about speed related to races of 800 meters and up. And since racing is our end goal, we’ll start there.

It’s helpful to conceptualize speed in terms of race pace. Intuitively, when we think of speed, we think of “faster than.” And that’s a good way to frame our definitions.

So, if race pace is the goal, then we have four broad types of speed:

Specific Speed – Paces that are 1–5% faster than race pace.

Supportive Speed – Paces that are ~10% faster than race pace.

General Speed – Typically 15%+ faster than race pace (strides count, but sprints do not).

Pure Speed – Maximum sprinting speed, sustained for less than 6–8 seconds.

Note: These are the terms I prefer to use. Various coaches who’ve influence my thinking—such as Skiba, Canova, Coe, and Pfaff—use different terminology to describe similar concepts. The key takeaway is understanding the concept and not fixating on the labels (says the guy writing about how runners misuse terms).

If you’re more of a visual thinker, imagine a pyramid with race pace as the apex. On the left side, we have endurance, covering slower than race paces. On the right side, we have our types of speed, covering faster than race paces.

Thinking about speed in this context is helpful for two reasons.

First, it’s a system that allows us to consider what speed means in the context of any race distance. This thought process is as helpful for the 1500m as it is for the marathon. It provides a hierarchy of importance we can utilize as we design training.

Second, it clarifies what we mean when we say speed. Specifically, speed means paces that are faster than race pace. It never means a pace slower than race pace. And how far above race pace we are determines what type of speed we’re training.

Why Does This Matter?

Approaching training from a framework of principles rather than a standard formula makes training far more effective and adaptable. Contextualizing speed in terms of race pace is one part of that framework.

Let’s take a step back and talk about the most important principle of training:

Good training must be specific to the event we plan to race, meaning it should focus on individual and event-specific performance limiters.

That’s a fancy way of saying that if you’re training for a marathon, it doesn’t make sense to do 200s at mile pace as your last key session before the taper.

So what does this have to do with speed?

For almost every runner, aerobic development—not speed—is the primary performance limiter. More specifically, the biggest constraints tend to be critical speed and the pace at which an athlete surpasses lactate threshold (LT2 and LT1, commonly known as threshold and aerobic threshold, respectively. For Daniels fans, roughly “T” pace and “M” pace).

Pure, general, and even supportive speeds are rarely the key performance limiters in events longer than 800 meters.

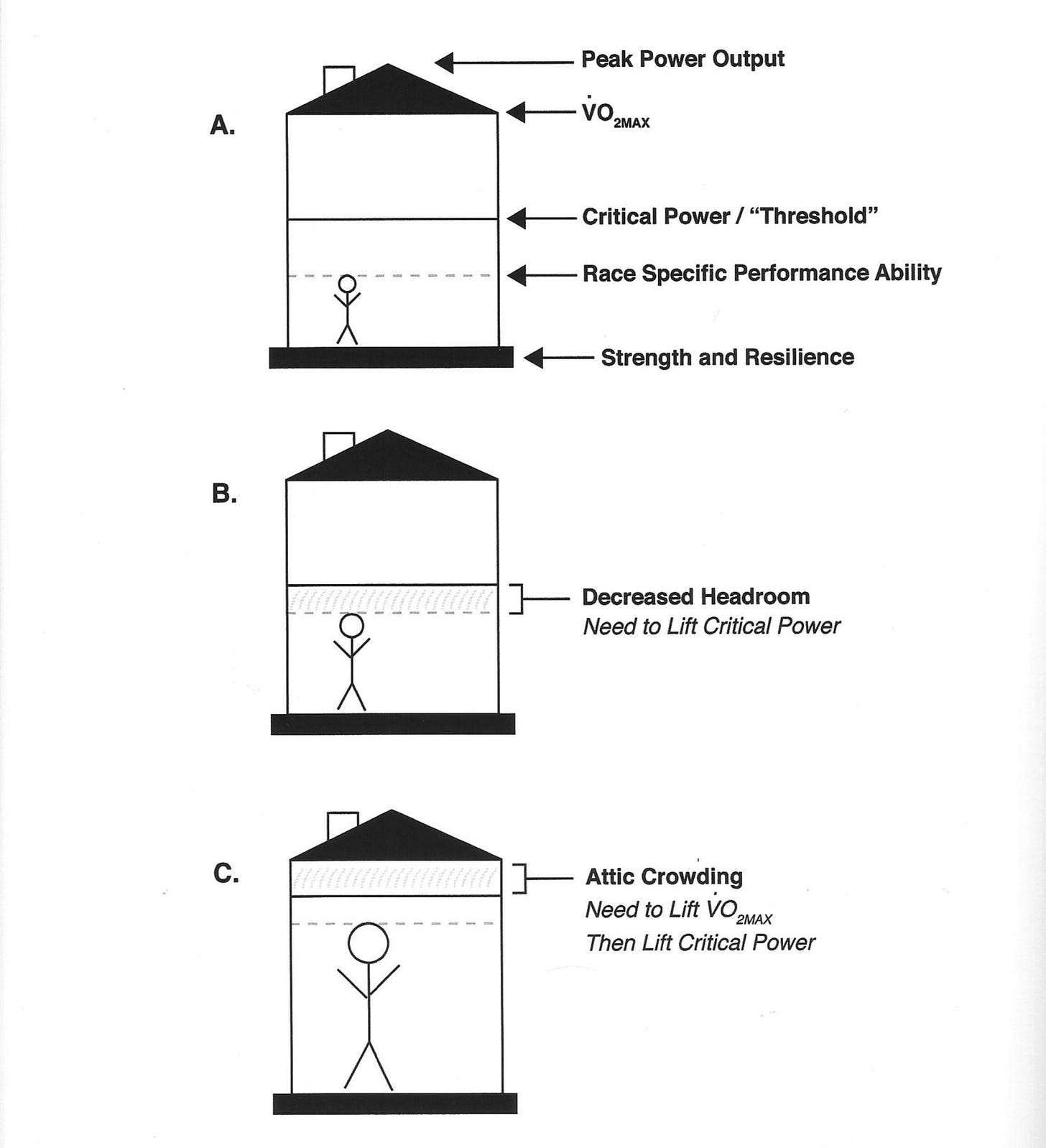

Dr. Phil Skiba has a great graphic in his book Scientific Training for Endurance Athletes we can use to illustrate this idea for a marathon runner:

In that illustration, general speed (in this case, think 3K-5K pace) falls somewhere around “VO2max.”

For runners who have not yet established massive aerobic strength (Figure A), prioritizing general speed is unlikely to yield significant improvements in marathon performance. Instead, the impact of general speed becomes slightly more meaningful only after a runner has undergone substantial aerobic development and is much closer to their genetic potential. Even then… general speed isn’t the key limiter.

In the real world, this framework for speed helps evaluate training approaches. Some popular marathon plans finish with six weeks of V02max focus. That’s a general speed in the context of marathon performance, and it's pretty implausible that it is a performance limiter that late in a marathon build.

Focusing on general speed during the training period most influential on race performance makes about as much sense as finishing a 1500m training block with six weeks of high-volume marathon-paced workouts.

Key Takeaway: General speed is not a great “bang-for-the-buck” use of time for most runners. It demands significant intensity and recovery, often at the cost of more important aerobic development.

Note: I’m not advocating that we should never do general or supportive speeds. I am arguing that they are a poor, yet common, choice of focus for most runners.

Why Developing Pure Speed Is Worth It

Here’s the thing. Developing pure speed is extremely useful. If you think back to the speed pyramid, it is the foundation we build on.

At this point, you might think, “So you’re telling me that it’s a waste of time to focus on VO2max work in a marathon, but it’s worth developing my 60m sprint? How does that make sense?”

First, we can develop pure speed without focusing on it. This can be done with less training load and recovery time than developing general speed, meaning it doesn’t have to detract from aerobic volume.

Second, science backs up the idea that sprinting is important— among athletes of similar 5K/10K ability, 100m sprint times are a stronger performance indicator than VO2 max.

Finally, we know that sprinting, explosive training (like plyometrics), and heavy resistance training significantly improve running economy, which is a massive factor in running performance.

Developing pure speed will increase your peak power output. It will increase the amount of creatine phosphate in your muscles. It will signal for adaptation in muscle fibers you don’t typically recruit in your running. It will improve your neuromuscular system. It will increase your speed reserve, allowing your muscle fibers to handle race pace at a lower percentage of overall power.

These improvements won’t create overnight breakthroughs, but over time, you’ll feel smoother, more elastic, and better able to change gears.

How Do We Develop Pure Speed?

Okay, enough theory. For most recreational runners, how should we go about developing pure speed?

Well… we need to run really fast. Sprint, actually. And we need to do that once or twice per week. And if you can, you should add some heavy lifting and plyometrics into your week.

Note: Strides do not develop pure speed. The way most runners do strides—10-20 seconds of fast running at or slightly faster than mile pace with ~60-90s recovery—targets general speed but doesn’t do much to develop it. You’ll get some of the same adaptations as pure speed development (improved neuromuscular system, improved running economy) but fail to get others (improved creatine phosphate system, increased muscle fiber recruitment). I think strides have their place, but given the option, I’d rather have most runners focus on pure speed. Pure speed development is better at improving coordination, mechanics, and general athleticism, not to mention max speed and power.

Here’s the general approach I take for distance runners who have never sprinted before:

Introduce high-speed running: Start with 3–4 strides post-easy run (10–15 seconds of smooth, relaxed, fast running; ~90 seconds recovery). Perform 2–3 sessions per week for two weeks, then progress to 5–6 strides per session for two additional weeks.

(Optional, but recommended) Introduce sprint mechanic drills: Implement drills before strides to refine technique (e.g., A-skips, B-skips, bounding). Sprinting is a skill you can develop, and these drills will help. This video is a great place to start:

Introduce hill sprints: Find a moderately steep hill. Sprint 6–8 seconds at ~98% effort, recover 3–4 minutes, and repeat 3–4 times. Gradually build to 4–6 reps per session. Don’t skimp on the recovery. Most distance runners feel weird standing around for 3 minutes, but it’s essential. Sprinting for 6-8 seconds depletes the creatine phosphate system, which is the system we want to develop. That system takes about 3 minutes to recharge. If you don’t take the recovery, you’re training the wrong system. Slot these in on easy days. I like to do them the day before aerobic workouts; it’s a good way to get things primed. Add 1-2 more sprints every other week until you get to 4-6.

(Optional) Progress to flat sprints: I rarely recommend flat sprints for injury-prone or masters runners or those deep in a marathon cycle, where the risk outweighs the benefit. If you opt for these, swap hill sprints for flat sprints—the same volume, duration, and rest. Focus on mechanics.

This approach requires minimal training load yet delivers long-term benefits for all distance runners. It also provides an excellent foundation for shorter races; it’s easier to introduce mile-supportive speed when you’re used to sprinting uphill!

Final Thoughts

Incorporating pure speed development into your training for a few months can unlock noticeable improvements— hearing “I have so much more pop now” is common among runners who I’ve introduced to sprinting. It refines your mechanics, enhances neuromuscular coordination, and builds a stronger foundation for faster running.